Krazy is a black cat. Ignatz is a white mouse. The cat is in love with the mouse, the mouse, however, hates the cat and is most content when beaning the cat with a brick. Meanwhile a cop, who happens to be a dog, and who also happens to love the cat, tries his best to disrupt this daily routine and stop them from reaching that inevitable final panel. Within this repetitive simple framework, and for over 40 years, George Herriman layered lyrical dialogue, shifting surreal backgrounds, social commentary, abstract cultural symbolism, and, evidently, ruminations on identity.

In its time, Krazy Kat was never particular popular; when the final strip ran in 1944, it appeared in less than 40 newspapers. So how did it survive for so long? It was often regulated to the arts section, away from the more universally agreed funnier comics, which maybe points to the secret to its longevity. America's "intellectuals" loved it, and so did the famous newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who kept Herriman's career going despite the falling numbers.

Perhaps it was due to this unpopularity or vague feeling of "artiness" that Herriman was able to get away with the experimentation that he did. Plenty of readers admitted to "not getting it," but if they had, how would the themes of the strip have come across at that time, or where they even noticeable in the daily, disposable way they were being parceled out?

It was a secret during George Herriman's lifetime that he was Creole; something he supposedly kept to himself because of the hostile times hes lived in, often claiming he got his looks from time spent in Greece. But later historians and fans, in light of the discovery of his ancestry, have devoted a lot of writing to re-examining his work within the context of race. For instance, was Krazy a black cat or actually being coded as black? Chris Ware argues that actually, yes, people would've picked up on this aspect in the 1920s; he even makes the argument that, to audiences steeped in that culture of the early 1900s, Krazy possibly read as an African American character, even a stereotype.

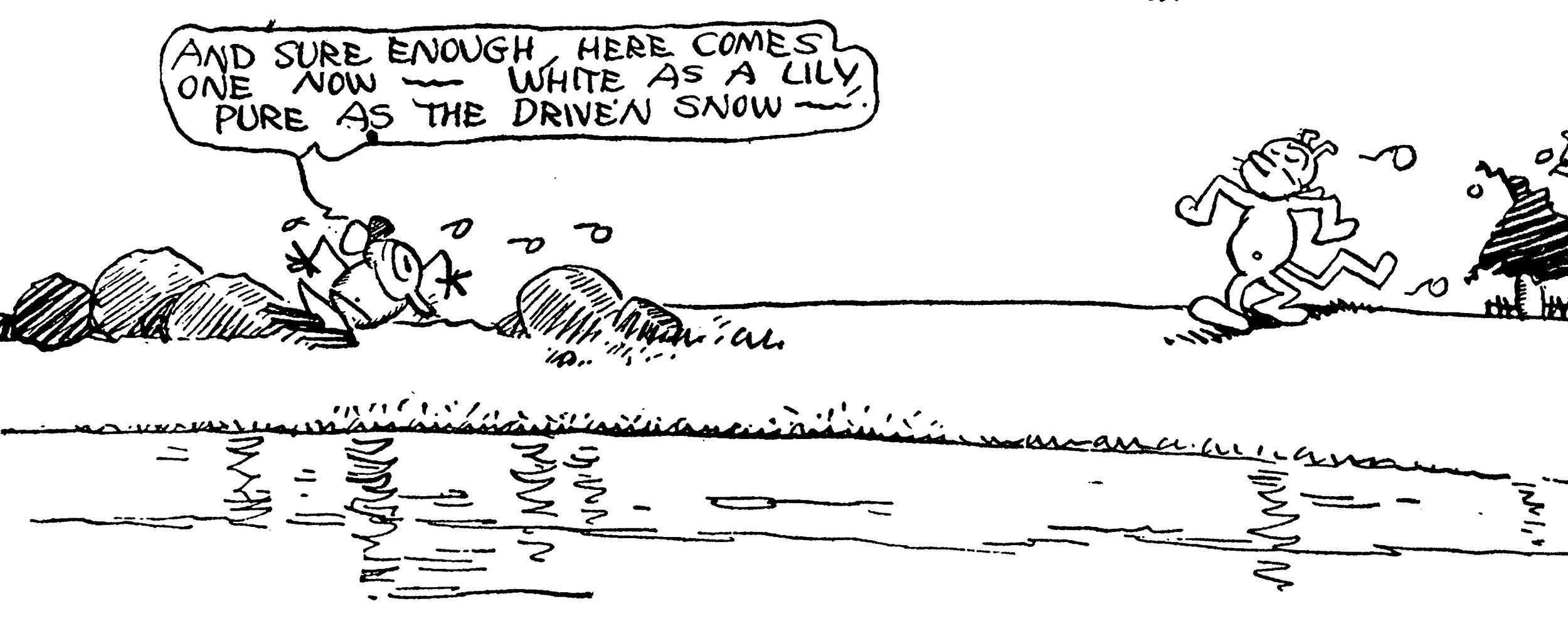

There's a reoccurring motif of Ignatz finding himself attracted to Krazy only after Krazy's fur has turned white. I found at least two Sunday page examples. One from 1921 finds Krazy turned white by an accident with whitewash:

And another from earlier, 1918, in which Krazy purposely patrons a salon to have their fur bleached:

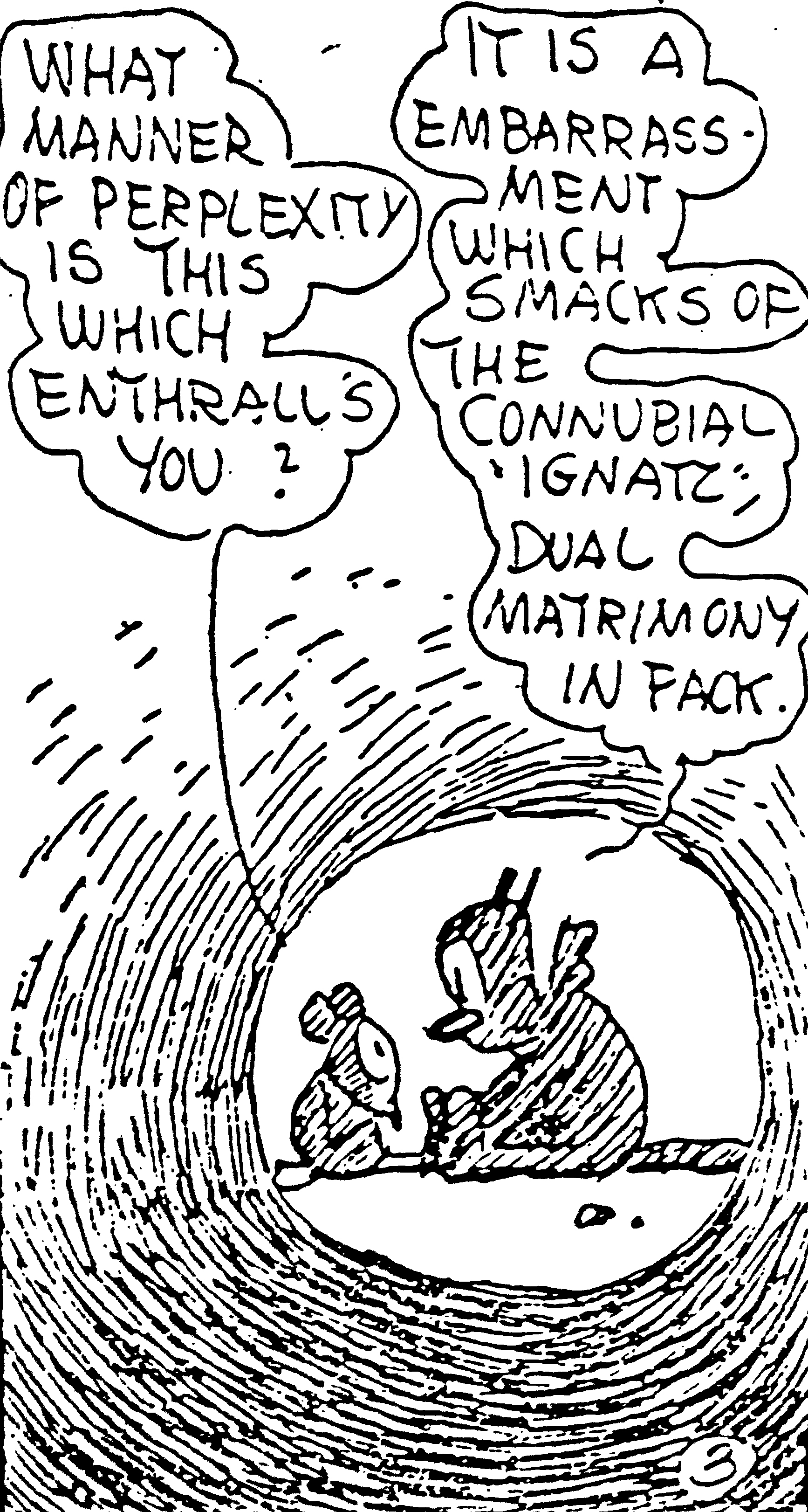

This comic also serves as example of the other way Krazy Kat addressed identity, and that is the way it questioned and played with Krazy's gender. In some strips, Krazy is male, in others, Krazy is female. Sometimes these shifts in gender were to serve that strip's particular story. For example, when Krazy needs to wear a dress for a ball, she is a she, but when Krazy dresses to drive a car, he is a he.

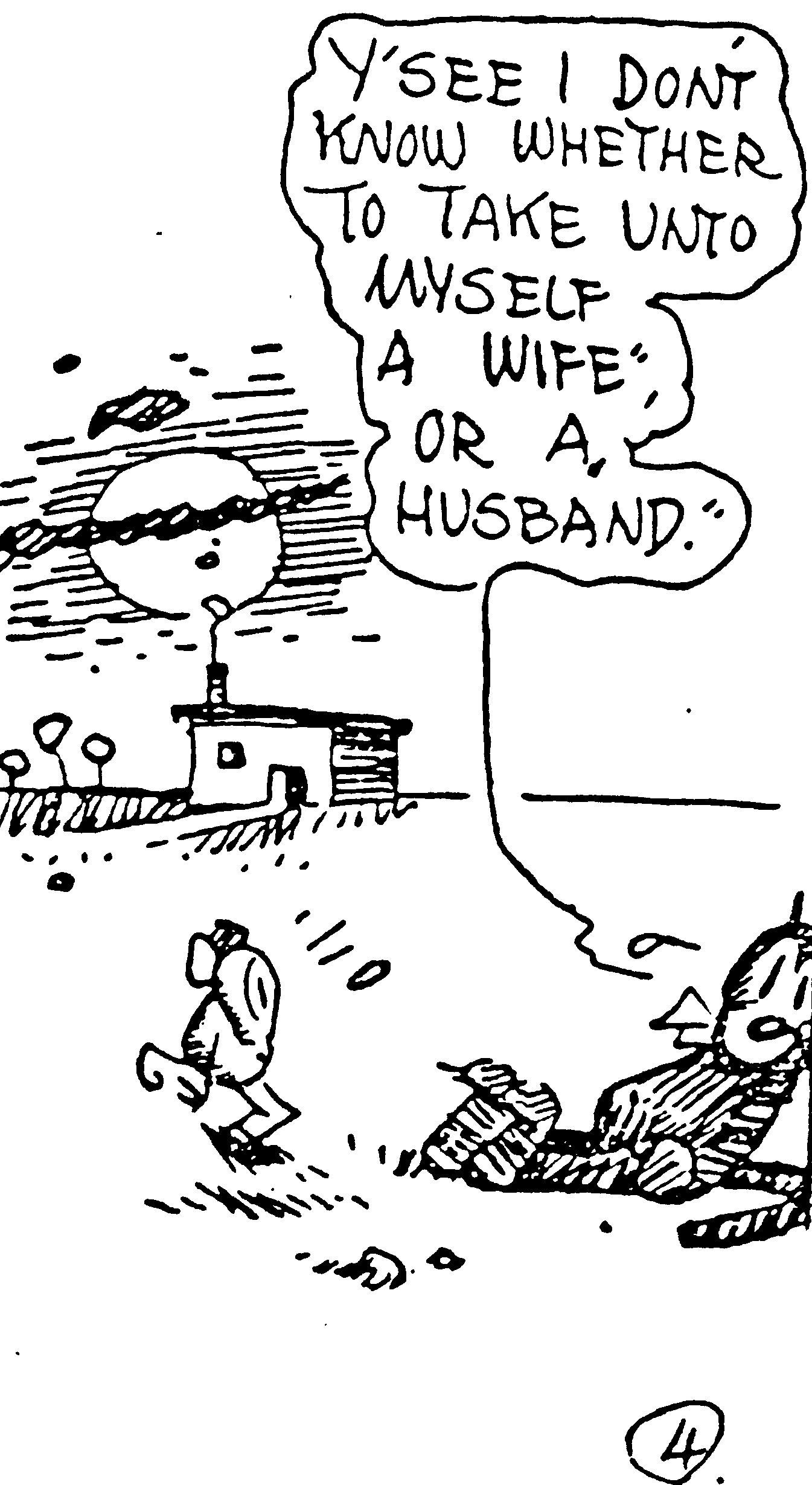

But this isn't always the case, as pronouns used for Krazy (by both themselves and other characters) could change several times in just one strip, meaning that a male character frequently openly declared love for another male character. Various supporting cast attempt to discover what Krazy identifies as and are perplexed or discouraged by Krazy's refusal to label themselves. In a daily strip from 1915 (only five years after the duo's first appearance), Krazy laments to Ignatz (quite plainly) that they don't know if they want to "take unto a wife or a husband." Probably the only thing in Krazy Kat that changed more often between panels than Krazy's gender were those famous shifting desert backgrounds.

As Krazy Kat was adapted into other mediums-- in particular mediums with sound-- creators were faced with the challenge of how to present Krazy and their fluid gender. Their answer, for the most part, was to pretty much ignore the aspect entirely. Except for one entry that did attempt to capture the strip in animated film, most of the cartoons released by Columbia Pictures in the 1930s were more along the lines of a generic Mickey Mouse or Felix the Cat analogue, casting Krazy as male with another cat serving as his Minnie-esque love interest.

Another series of cartoon shorts, released by Kings Features Syndicate in the 1960s, attempted to capture the trappings and imagery of the strip if not quite the spirit. This iteration of Krazy was quite clearly female and voiced by a voice actress named Penny Phillips.

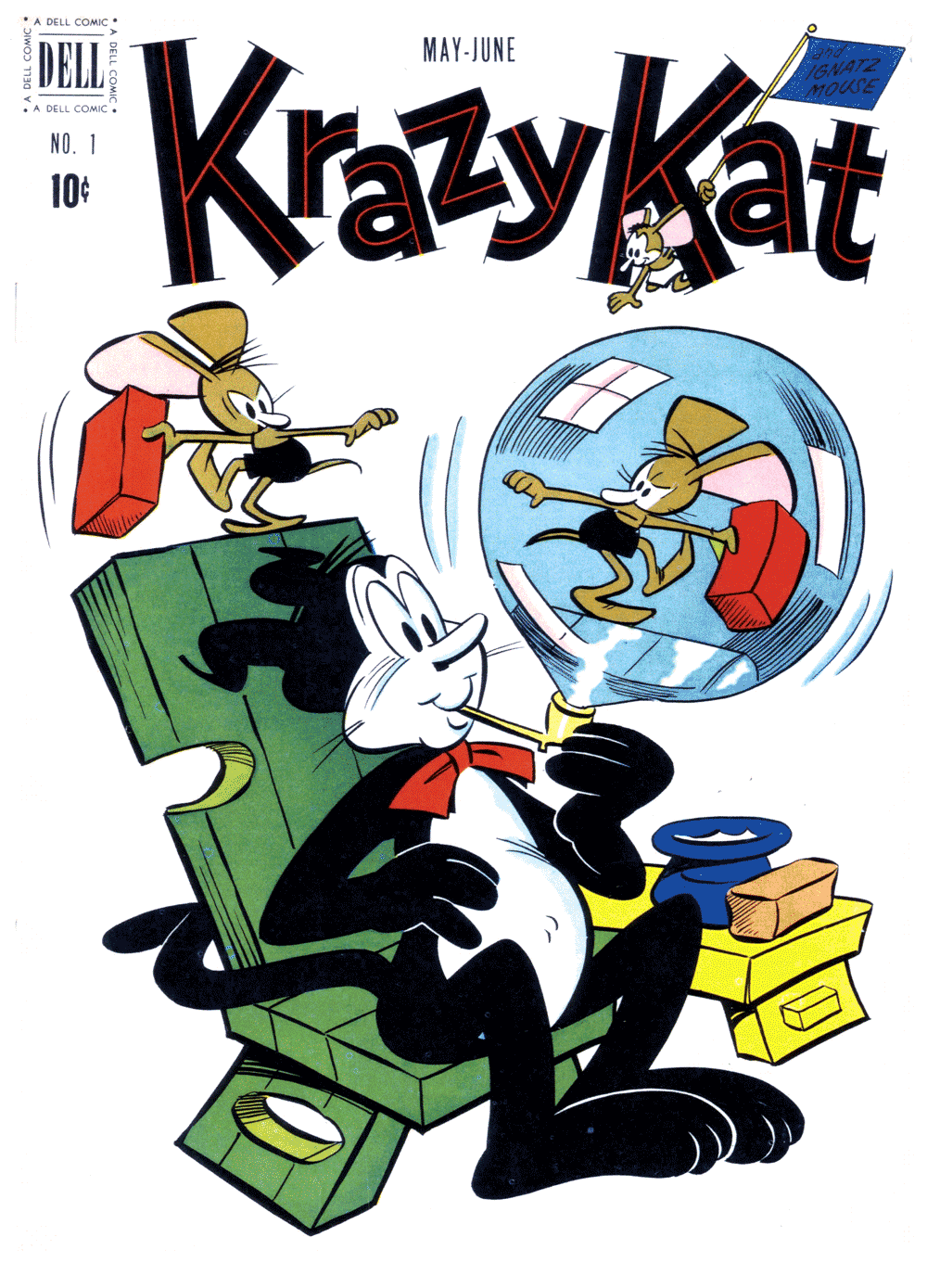

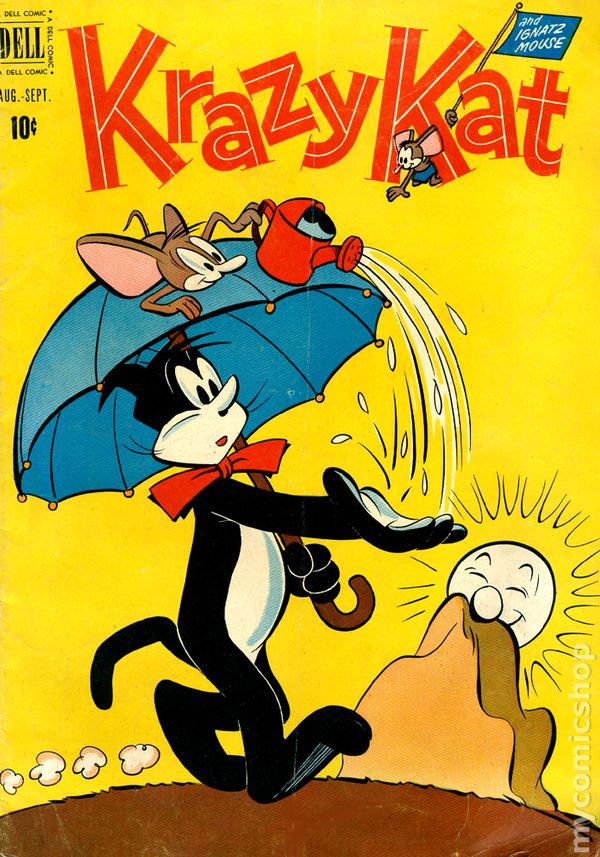

A Dell Comics series in the 1950s, written and drawn by John Stanley, casts Krazy as male, turning Krazy and Ignatz's relationship into more of a frenemy vehicle for slapstick situations and seemingly dropping the romantic angle. In Jay Cantor's 1988 novel, Krazy seems to have been given the definitive pronoun of "her."

How much of Krazy was a cypher for Herriman's musing on his own identity, or at least the idea of how one chooses to present themselves? Herriman put a lot of what interested him into his work-- from tall tales to poetry to Navajo art to the deserts of Arizona, so it would be silly to argue that identity wasn't something Herriman actively sought to explore.

Herriman died in 1944, long before the discovery of his race in the 1970s, so we can't ask him how he thought of himself. Krazy Kat can be read and enjoyed without any of these questions in mind, of course, and the strips focusing on identity-- race, gender, status-- aren't so much about hiding your true self as they are about showing the malleability of identity.

When asked by the director Frank Cappa, just what is Krazy Kat's gender, Herriman had this to say, "I fooled around with it once; began to think the Kat is a girl—even drew up some strips with her being pregnant. It wasn’t the Kat any longer; too much concerned with her own problems—like a soap opera. . . . Then I realized Krazy was something like a sprite, an elf. They have no sex. So the Kat can’t be a he or a she. The Kat’s a spirit—a pixie—free to butt into anything."

Krazy and Ignatz make their first, unnamed appearance at the bottom of a different feature by Herriman, one of his many other comics before creating Krazy Kat. From this first comic, the poetic world and shifting deserts of Cococina County would one day grow, but for now, and for the duo's first several appearances, there was no deeper meaning. Barely more than doodles: a cat, a mouse, and a hurled brick. Though, in a way --even there, right from that vaudeville duo beginning-- the traditional roles of a cat and a mouse were already being reversed, their identities being questioned. Because it was the mouse who attacked the cat.

The images in this post are thanks to:

Krazy Kat: The Art of George Herriman and

Fantagraphics' Krazy and Ignatz collections